At last I know how to read and write my name…exclaims a delighted Kuku Kanyar. Kuku Kanyar, 65, is a Nuba Moro man who for the past three years has been attending literacy classes in Khartoum.

The Moro felt that their language and culture were under threat and would die unless they took active steps to preserve and strengthen it. So five years ago Nuba Moro Community, the Episcopal Church of Sudan and the Bible Society of Sudan got together to set up a literacy program. It has shown steady progress and has begun to change the lives and attitudes of the people “ both Christians and non-Christians“ who register and attend the classes.

The Moro are the largest people-group among the 100 or so Nuba groups in the Nuba Mountains, the hills that rise abruptly from the plains in Kordofan Province, Central Sudan. History records that the Nuba were pushed out of Dongola, many centuries ago by Arabs who had occupied and settled the area. Dongola was a province in Upper Nile (near the present Egyptian border) that was part of the old kingdom of Makuria. As they moved southwards, some Nuba took refuge in the Nuba Mountains, while others moved on further south. The groups who settled in the mountains developed their own “ mostly distinct “ dialects.

New Testament a Spur to Learning to Read

Each mountain thus became like an independent state for a particular group which had its own administration, language and culture. Among these mountain groups, the Moro tribe seized the Moro Hills, in the eastern part of Kadugli, and settled there, eventually becoming known as the Nuba Moro.

Today their numbers are estimated at more than 200,000, though they themselves believe they number twice that figure and Sudan’s unstable situation has ruled out a reliable census for a considerable time.

The orthography of the Moro language, developed by missionaries in the 1930s, paved the way for the translation of the New Testament in 1965 by the Bible Society in Sudan. Education in the area was at a low level, and the arrival of the New Testament was a spur to many to start learning to read. After independence in 1956, Arabic became the dominant language. In Kadugli and other towns in the Nuba Mountains, using local languages was considered “ahali”, primitive and undeveloped; school children heard using their mother tongue were punished with a flogging and the Nuba languages began to fall out of use.

Forgetting Their Culture

During the 21 years of Sudan’s civil war, the Nuba Moro, like other people-groups, were displaced from their ancestral lands. Half the population fled north to large cities such as Khartoum, Medani and Port Sudan, where they lived in poverty in camps for displaced people, while others moved south to join the rebel movement, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA).

The effect of the migration northwards was to mix the Nuba Moro with Arab Muslims who have their own strong Islamic culture. As result, many of the Moro, especially the younger generation, soon began to forget their culture, their language and their ancestral roots. As before, Arabic is the dominant language of the schools in the displacement camps and pupils using any other are given a public lashing as a warning to them and to others.

Government Backing

It was in these circumstances that the Nuba Moro Literacy Project was born. The objectives of the project are ambitious: it aims to publish learning resources and encourage the Moro community to learn to read, to encourage the Moro to write about their history and culture and, by doing so, to preserve it, and to promote the reading of the Bible in Moro so as to preserve Christianity among the people “ the urban young, in particular “ in the face of the growing influence of Islam.

The project has achieved much but more remains to be done. So far there are 19 literacy classes running in the Khartoum area. In the Nuba Mountains, literacy classes are run in primary schools in the evenings when the children’s classes are over. They have the full backing of the regional government; two Church schools make classrooms available for literacy training free of charge; a training college, the Isaac Kuku Academy, has been established to train literacy teachers and so far 23 teachers from the Nuba Mountains and 26 from Khartoum have been trained there. More teacher-training is taking place in other centres.

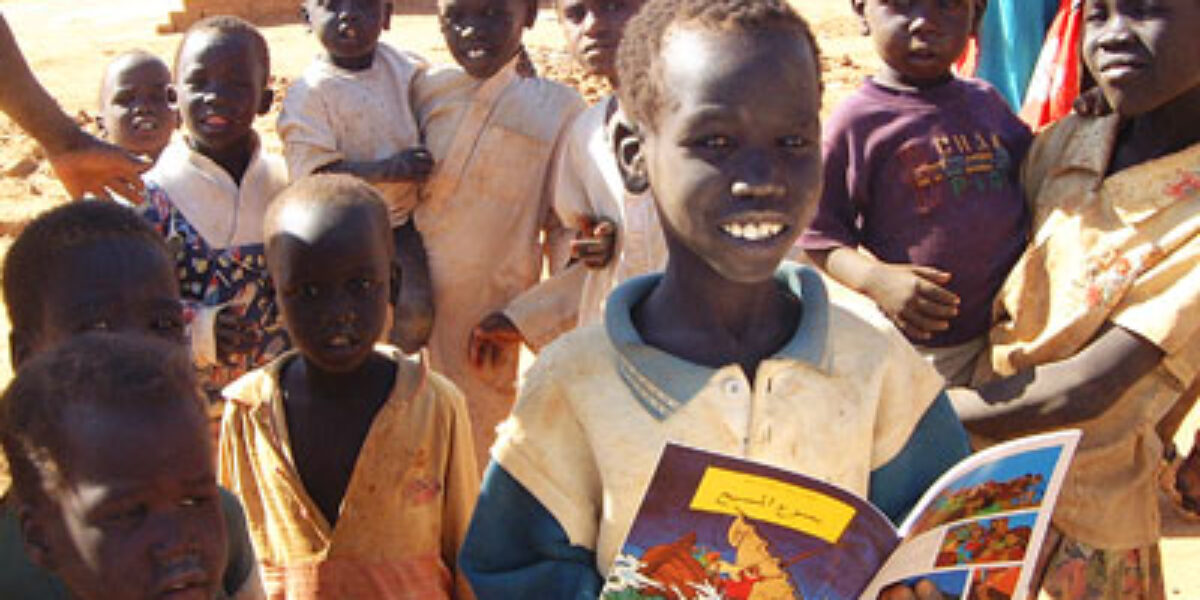

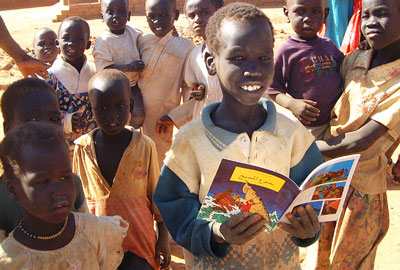

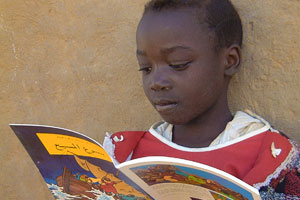

In addition to teachers being trained, new books have been published. Written by Moro teachers and Moro Bile translators, they cover the history of Moro culture and retell stories from the Bible and Moro folklore. In anticipation of the interest, some 40,000 copies have been printed.

Some 12,000 New Reader Portions have also been printed and distributed for use as textbooks for the emergent readers. desks, chairs, benches, blackboards and other resources have also been purchased by the project for use in the literacy centres in the Nuba Mountains.

The classes are proving very popular: many people, old and young, can now read and write as their preparation for the forthcoming publication of the Bible. Many people are also coming to know Christ through the program.

Struck by Jacob’s Dream

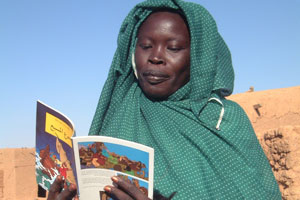

Risala Nooha is one of those learning to read. A mother of six children, she took her family to Khartoum for safety in the early 1990s when the war reached the area in which they had been living.

Risala could hardly believe that she could read the Bible Society’s trial edition of the Book of Genesis. What struck her most was the story of Jacob’s Dream at Bethel, recounted in Genesis 28. Until then, she confessed, she had never heard the story before. One day she wants to go back to her home in the Nuba Mountains, so Jacob’s vow to the Lord struck her with particular force, especially verses 21-22: “[If you] …bring me safely home again, you will be my God. This rock will be your house, and I will give you a tenth of everything you give me” (CEV).

Risala praises the Lord and vows to buy her own copy of the Bible and read it from Genesis to Revelation in her mother tongue. She wants her children to speak and write the Moro language – “our language” – too.

“My children seem to be lost in the years we have been in Khartoum,” she laments.

Angelo Ali, was formerly the Deputy Headmaster of the Senior Secondary school in Khartoum. He explains what made him resign from his post to become the Director of the Nuba Moro Literacy Project. His colleagues in the Ministry of Education were always telling him that in 15 years all the local languages, especially in those spoken in the Nuba Mountains, would die, replaced by Arabic.

“What they said was practically coming true,” he said, “and I felt obliged to take responsibility for reviving our language. I am happy that there is a light at the end of the tunnel. Now I am confident that our language will never die till Christ comes!”