The Gnostic ideas in The Da Vinci Code are not new. In fact, Irenaeus addressed these ideas thousands of years ago in his work Against Heresies.

The Bible did not arrive by fax from heaven. … The Bible is a product of man, my dear. Not of God. The Bible did not fall magically from the clouds. Man created it as a historical record of tumultuous times, and it has evolved through countless translations, additions, and revisions. History has never had a definitive version of the book. . . . More than eighty Gospels were considered for the New Testament, and yet only a relative few were chosen for inclusion—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John among them” (Da Vinci Code, 231).

These words by Teabing, one of the characters in Dan Brown’s The DaVinci Code who is the mouthpiece for 21st century Gnostics, challenge the idea of revelation and canon, much as his Gnostic counterparts did almost 2,000 years ago. Teabing goes so far as to say that Constantine “commissioned and financed a new Bible which omitted those gospels that spoke of Christ’s human traits and embellished those gospels that made him godlike. The earlier gospels were outlawed, gathered up and burned” (234). Despite Teabing’s historic hyperbole, it is true that in the fourth century Constantine did commission a new Bible. It is not true, however, that it was for the purpose of suppressing those other gospels. By the time of Constantine, the issue of what would be in included in the Bible had already been decided for the most part, reflecting the consensus agreed upon by most Christians from debates in earlier centuries. There were a few remaining books that were in dispute—none of which were Gospels.

Far from being able to suppress those competing Gospels, two centuries earlier, an orthodox minority was being challenged by the arguably more popular Gnostic sects of its day. One sect in particular, led by Valentinus, a one time contender for the bishopric of Rome, offered a challenge to orthodoxy that was so great and so infectious that the orthodox Bishop of Lyons, Irenaeus, took it upon himself to write A Refutation and Subversion of Knowledge Falsely So-called, otherwise known as Against Heresies. The recent discovery of the Nag Hammadi Library confirm many of Irenaeus’ claims about Gnosticism in his day. Brown’s Teabing would be happy to know that Irenaeus was not unaware of the plethora of Gnostic gospels he mentions:

But those who are from Valentinus who, being altogether reckless in putting forth their own compositions, boast that they possess more Gospels than there really are. Indeed, they have arrived at such a pitch of audacity as to entitle their comparatively recent writing, “the Gospel of Truth,” although it finds no agreement with the Gospels of the Apostles. They in fact have no gospel which is not full of blasphemy. If what they have published is the Gospel of Truth, it is still totally unlike those which have been handed down to us from the apostles . . . (Against Heresies 3.11.9).

Irenaeus argues that orthodoxy had chosen to limit the number of Gospels to four—no more (despite Marcion’s attempt to reduce the number to his mutilated Gospel of Luke)—no less (despite Gnosticism’s attempt to get their gospels equal time). But why four? Irenaeus points to the prevalence of the number four in both nature and Scripture. In nature, there are the four zones of the world in which we live, and four principal winds. He calls the “pillar and ground” of the Church “the Gospel under four aspects, but bound together by one Spirit” (Against Heresies 3.11.8). His scriptural argument focuses on the enigmatic cherubim spoken of in Ezekiel which had the face of a lion, a calf, a man, and an eagle. These four faces, he says, correspond to the subject matter of the four Gospels: John reflects the lion-like power and leadership of Christ; Luke takes up the sacrificial and priestly functions of Christ symbolized by the sacrificial calf; Matthew relates Christ’s human birth and genealogy; and Mark begins with the prophetic spirit of Isaiah pointing toward the gift of the Spirit hovering with the wings of an eagle over the Church (Against Heresies 3.11.8). Irenaeus also notes that the foundation on which these four Gospels rest is so firm that the very heretics themselves bear witness to them when they use them as their starting point for their own peculiar doctrine (Against Heresies 3.11.7). In other words, he says, anyone who reads the Gnostic gospels can see how derivative they are—and how bizarre in comparison to the four canonical Gospels.

In the first two books of Against Heresies, Irenaeus lays out the bizarre cosmological speculations and numerology of Gnosticism, unintelligible to common sense, but “revealed” to those who are the initiated. His critique is telling in how they construct their gospels:

They gather their views from other sources than the Scriptures; and, to use a common proverb, they strive to weave ropes of sand, while they endeavor to adapt with an air of probability to their own peculiar assertions the parables of the Lord, the sayings of the prophets, and the words of the apostles, in order that their scheme may not seem altogether without support. In doing so, however, they disregard the order and the connection of the Scriptures, and so far as in them lies, dismember and destroy the truth. By transferring passages, and dressing them up anew, and making one thing out of another, they succeed in deluding many through their wicked art in adapting the oracles of the Lord to their opinions (Against Heresies 1.8.1).

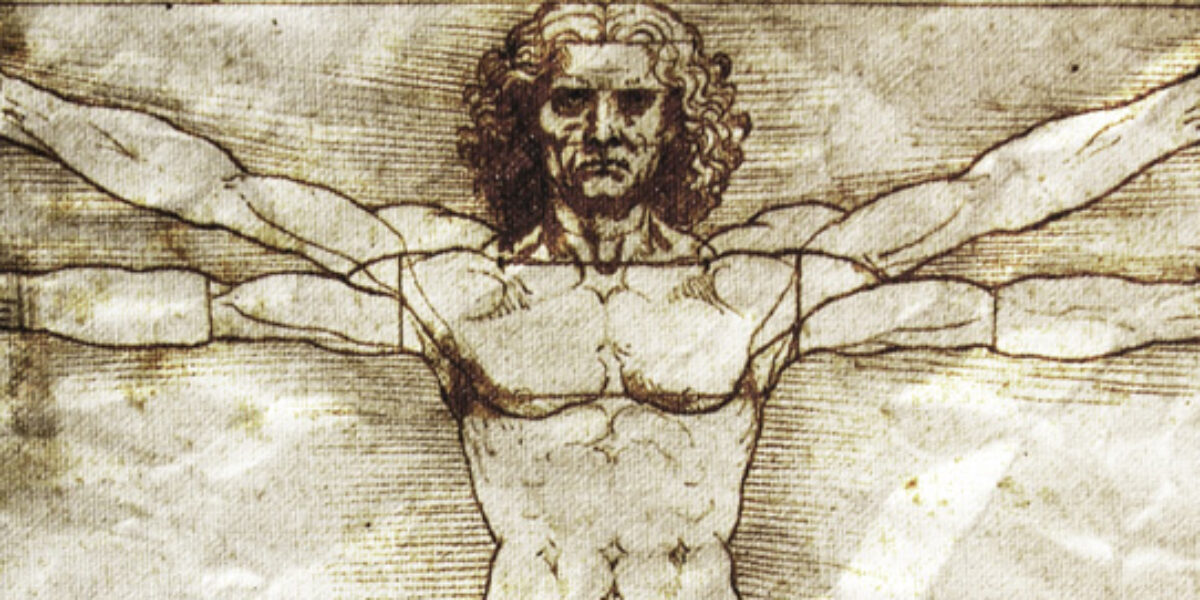

He further likens the Gnostics’ treatment of Scripture to that of taking a beautiful picture of a king and rearranging the tiles into a dog or fox. Their “gospel,” in other words, is one created in their own image—and a very poor image at that. Gnosticism, at its core, creates God and revelation in its own image. Faith, then and now, needs something more solid to cling to. The Gnostic gospels to which Teabing would have us return, however, are only ropes of sand. And for those of us who are often only holding on to life by a thread as it is, a rope of sand just won’t do.

by Joel Elowsky, Operations Manager

Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture,

Drew University, Madison, NJ