There are more copies of Bibles than any other book in the world. Read about how the Bible was passed down to us through countless generations over thousands of years.

The Bible is like a small library that contains many books written by many authors. The word “Bible” comes from the Greek word biblia, meaning “books.” It took more than 1,100 years for all of these books to be written down, and it was many more years before the list of books now known as the Bible came together in one large book.

Passing Stories Along

Before anything in the Bible was written down, people told stories about God and God’s relationship with the people we now read about in the Bible. This stage of passing on stories by word of mouth is known as the oral tradition. This stage of relating stories by word of mouth lasted for many years as families passed along the stories of their ancestors to each new generation. In the case of the Jewish Scriptures (Old Testament), some stories were told for centuries before they were written down in a final form.

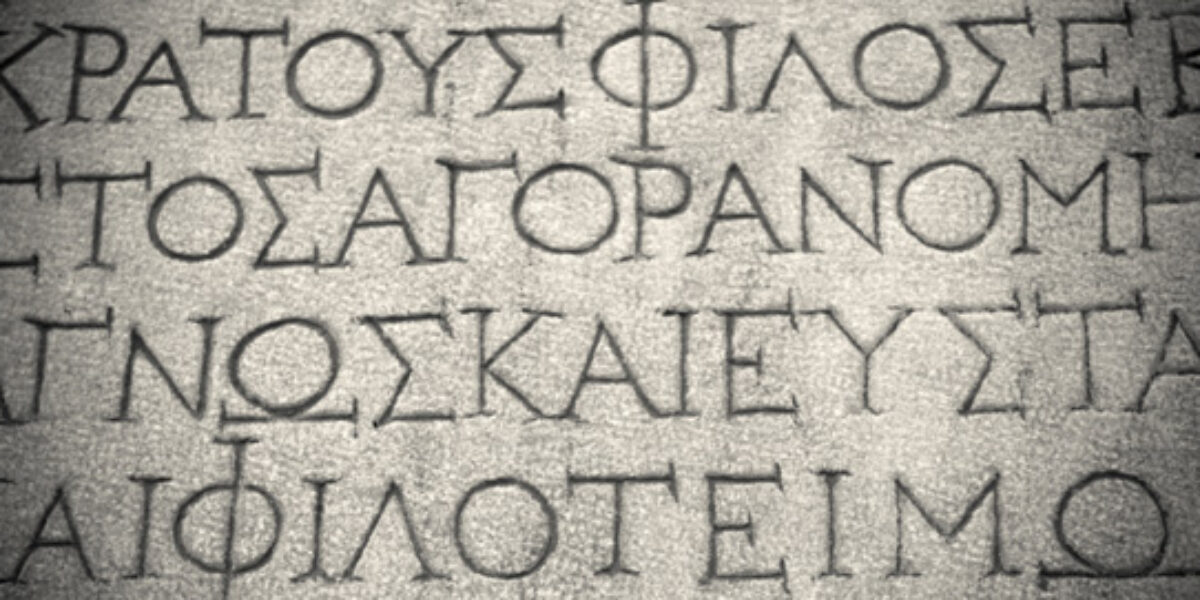

Writing Down the Bible Stories

Eventually, as human societies in the Near East began to develop forms of writing that were easy to learn and use (around 1800 B.C.), people began to write down the stories, songs (Psalms), and prophecies that would one day become a part of the Bible. These were written on papyrus, a paper-like material made from reeds, or on vellum, which was made from dried animal skins. But all the books found in the Old Testament were not written down at one time. This process took centuries. While some books were being written and collected, others were still being passed on in storytelling fashion. Since these stories were sometimes written in a piecemeal fashion, and since sometimes more than one version of a story was collected, parts of the Bible can be confusing to modern readers. For example, compare Genesis 1:1-24 to Genesis 2:5-3:24, and 1 Sam 16:14-23 and 1 Sam 17:55-58.

The very first manuscripts of the books that make up the Old and New Testaments have never been found, and most likely wore out from continued use or were destroyed centuries ago. However, copies of these manuscripts were made by hand and became valued possessions of synagogues, churches, and monasteries. Before these copies wore out new copies were made, and then eventually copies were made from these copies-and so on, from one generation to the next. Some very old copies of both the Old and New Testament writings have been preserved, and they are now stored in museums and libraries around the world in places like Jerusalem, London, Paris, Dublin, New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Ann Arbor, Michigan, Greece, Italy, Russia, and Sinai.

Once the stories of the Bible began to be written down, it became necessary to make new copies before the old ones wore out from repeated use and became unreadable. Sometimes several scribes made copies while another scribe read the text aloud.

Collecting the Jewish Scriptures

It is not possible to know exactly when all the books of the Jewish Scriptures were finally collected. Some of the writings in the Jewish Scriptures may go back as far as 1100 B.C., but the process of bringing the books together probably didn’t begin until around 400 B.C. This collecting of books continued while new books were being written as late as the second century B.C. The process of deciding which books would be part of the official Jewish Scriptures went on until almost A.D. 100. This work was often done by Jewish rabbis (teachers).

Preparing the Bible for a Changing World

It was during this time that the Jewish Scriptures were translated into Greek. This translation is called the “Septuagint”, which means “seventy,” and is often identified by the Roman numeral for seventy (LXX). The legend of how the Septuagint came to be, and how it got its name is told in a document called the “Letter of Aristeas.” The legend says that seventy-two scholars began translating the Jewish Scriptures from Hebrew, all at the same time. The “Letter” goes on to say that they all finished at the same time, in seventy-two days, and that all seventy-two scholars discovered that their translations were exactly the same! All the seventy-some numbers in this story gave the translation its name. This Greek version of the Bible was used by Jewish people scattered throughout the Roman world, because most of them spoke Greek instead of Hebrew. The oldest copies of the Septuagint date from the second century B.C., more than one hundred years before Jesus was born. The Septuagint was also the main version of the Jewish Scriptures used by early Christians.

It is not clear how it was decided which books should be considered holy enough to be included in the Jewish Scriptures. We do know that around A.D. 100, a group of Jewish scholars were meeting at Jamnia, a center of Jewish learning west of Jerusalem. During this time, the scholars were debating which books should be in the Jewish Scriptures. Probably these scholars’ discussions were a large part of the Jewish community’s decision that thirty-nine books should be on the holy list (canon). Seven books, sometimes called the Deuterocanonical books (meaning second list), were not included on the list. Today, most Protestant churches follow the original list of thirty-nine books and call it the Old Testament. The Roman Catholic, Anglican (Episcopal), and Eastern Orthodox churches include the Deuterocanonical books in their Old Testament. For more about this see the article What Books Belong in the Bible?

The Stories of Christ and His First Followers

Jesus and his earliest followers were Jewish, and so they used and quoted the Jewish Scriptures. After Jesus died and was raised to life around A.D. 30, the stories about Jesus, as well as his sayings, were passed on by word of mouth. It wasn’t until about A.D. 65 that these stories and sayings began to be gathered and written down in books known as the Gospels, which make up about half of what Christians call the New Testament. The earliest writings of the New Testament, however, are probably some of the letters that the apostle Paul wrote to groups of Jesus’s followers who were scattered throughout the Roman Empire. The first of these letters, probably 1 Thessalonians, may have been written as early as A.D. 50. Other New Testament writings were written in the late first century or early second century A.D.

The New Testament books were written in Greek, an international language during this period of the Roman Empire. They were often passed on and read as single books or letters. For nearly three hundred years A.D. 100-400, the early church leaders and councils argued about which New Testament writings should be considered holy and treated with the same respect given to the Jewish Scriptures. In A.D. 367, the bishop of Alexandria named Athanasius wrote a letter that listed the twenty-seven books he said Christians should consider authoritative. His list was accepted by most of the Christian churches, and the writings he named are the same twenty-seven books that today we call the New Testament.

Translating the Bible

When the New Testament books were written, the Greek language was understood all over the Mediterranean world. But by the late second century A.D., local languages were becoming popular again, especially in local churches. Translations of the Bible were then made into Latin, the language of Rome; Coptic, a language of Egypt; and Syriac, a language of Syria. In A.D. 383, Pope Damasus I assigned a scholar priest named Jerome to create an official translation of the Bible into Latin. It took Jerome about twenty-seven years to translate the whole Bible. His translation came to be known as the Vulgate and served as the standard version of the Bible in Western Europe for the next thousand years. By the Middle Ages, only scholars could read and understand Latin. But by the time Johannes Guttenberg invented the modern printing press (around 1456), the use of vernacular (local or national) languages was becoming acceptable and widespread in official, educational, and religious settings. And as more people began to learn to read, there was a new demand for the Bible in vernacular languages. And so translators like Martin Luther, William Tyndale, Cassiodoro de Reina, and Giovanni Diodati began to translate the Bible into the languages that people spoke in their everyday lives.

The process of Bible translating continues today, and it has been helped by some recent discoveries. For example, many ancient Greek manuscripts of the New Testament have been found in the last 150 years. In 1947, some very old manuscripts of the Jewish Scriptures were found in caves at Qumran, Murabba’at, and other locations just west of the Dead Sea in Israel, and have become known as the Dead Sea Scrolls. These manuscripts, which date from between the third century B.C. and the first century A.D., have helped modern scholars to better understand the wording of certain texts and to make decisions about how to best translate specific verses or words.

The Bible is a very old book that has come to us because many men and women have worked hard copying and studying manuscripts, examining important artifacts and ancient ruins, and translating ancient texts into modern languages. Their dedication has helped keep the story of God’s people alive.