Even before the time of Jesus, Jewish teachers had discussed the Law of Moses and whether there were one or more commands that summarized the whole law. This debate is easily seen in the Gospels of Matthew and Mark. The debate also seems to be behind Luke’s account, which immediately precedes the parable of the Good Samaritan.

Before the time of Jesus, Jewish teachers had discussed the relative importance of the many specific rules of the Mosaic Law and whether there was one or a few commands that were comprehensive of all the commands. In the synoptic Gospels, this debate is more easily seen in the Matthean and Markan accounts of the discussion about the “Great Commandment,” but it would appear to be behind Luke’s account also, which immediately precedes the parable of the Good Samaritan.

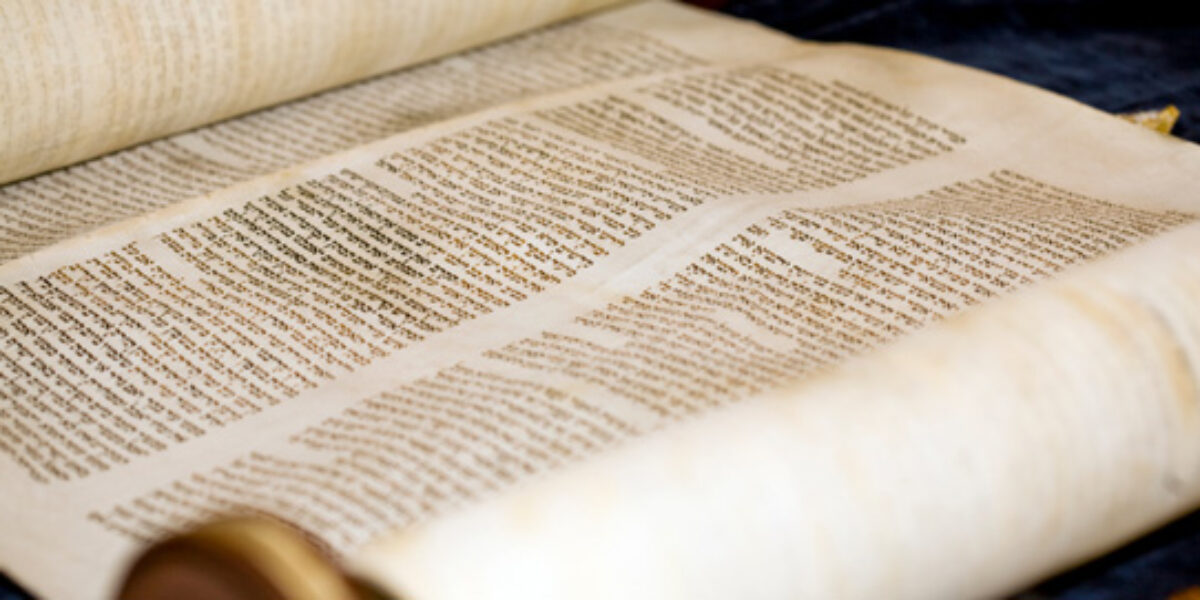

This article will examine discussions about the relative importance of each of the specific laws in the Torah as well as attempts to establish one or a few of the laws as comprehensive of God’s demands. It will look at these discussions in Jewish non-canonical literature and in Christian works outside the synoptic Gospels. All these sources are undated, and the rabbinic materials are notoriously hard to date. Thus it is usually not possible to say whether one statement preceded another or to suggest any possible influence on the synoptic Gospels (or vice versa). But these discussions will illustrate that the issue of locating a “great commandment” was under debate apart from Christian interest, and they will also offer illustrations of how some non-Christian teachers proposed to resolve the question.

The Most Important Command

Rabbi Simlai said that Moses communicated 613 precepts: 365 negative ones, which correspond to the number of days in a year, and 248 positive ones, which correspond to the number of parts of a man’s body. He based his argument upon Deuteronomy 33.4, which he interpreted with gematria so as to arrive at this number (bTalmud Makkoth 24a).

This belief that the Law contained 613 commandments led to a discussion of whether all commands were equal or whether some were of greater importance than others. In bTalmud Nedarim 32a, Rabbi Simlai said “Great is circumcision, for it counterbalances all the [other] precepts of the Torah, as it is written, ‘For after the tenor of these words I have made a covenant with thee and with Israel’” (Exod 34.27). According to one editor of the Talmud, this shows that circumcision is equal in importance to “all these words,” i.e., all God’s commandments.

Because of the Jewish belief that all of the Torah (written and oral) came from God, there was also most often the belief that all of the Torah was equal in importance. In pTalmud Qiddushin 1:7, Rabbi Abba bar Kahana says that Scripture makes all commands equal, so that the easiest have the same consequence as the most difficult. This is true both in respect to blessings promised and punishments threatened (so also in the same passage, Rabbi Simeon b. Yohai).

The Comprehensive Commandment

Yet some commands were thought to be more comprehensive than others, and, thus, to keep these commands would necessarily involve keeping the whole of the Mosaic Law.

In Pirke Aboth 1:18 (one of the earliest tractates in the Talmud), Rabbi Shimon b. Gamliel said: “Upon three things the world stands, on Truth, on Judgment, and on Peace. As it is said: Truth and judgment of peace judge ye in your gates” (Zech 8.16). According to translator Robert Herford, this is the first statement in Aboth using a citation of the biblical text. He adds, “In the present instance we may perhaps say that Simeon b. Gamliel pointed to Zechariah VIII.16 as a good summary of the essentials of human life, and framed his dictum accordingly.”

In Leviticus Rabbah 24.5, Rabbi Levi taught that all the Torah is summarized in one chapter, Leviticus 19, and he shows how all of Exodus 20—the Ten Commandments—is included in this chapter. In subsequent discussion Rabbi Levi and Rabbi Tanhuma saw that in three chapters Moses gave all of the Torah [Exodus 12; 21; Leviticus 19] because each one contains sixty specifications of religious duties (or some say 70 in each chapter). Then Rabbi Simlai says that David comprehended all the commands in eleven commands (in Psalm 15), Isaiah in six (in Isa 33.15), and Micah in only three (Mic 6.8, also noted by Jesus in Matt 23.23). Then Isaiah 56.1 is said to have comprehended all the commandments in just two: “Observe justice and do righteousness”; and finally, Amos 5.4 and Habakkuk 2.4 in just one statement. (Habakkuk 2.4 is, of course, also important for Paul in Romans 1.17 and Galatians 3.11.)

Perhaps the most famous rabbinic summary of the Law is the familiar story of the pagan who goes to the two leading rabbinic school leaders, Shammai and Hillel, asking each one to teach him the whole of the Torah while he stands on one foot. While Shammai rebuffs the man for his insolence, Hillel replies, “What is hateful to you, do not to your neighbor; that is the whole Torah, while the rest is commentary thereof; go and learn it” (bTalmund Shabbath 31a; many have noted the similarity to Matthew 7.12 and the “Golden Rule”).

But there also are other attempts to find a single verse or command which encompasses all that the Mosaic Law demands. For example, in Genesis Rabbah 24, Rabbi Ben Azzai said that Genesis 5.1 “represents the encompassing principle of the Torah” [since it shows that all of humanity comes from a single progenitor]. In the subsequent discussion, Rabbi Akiba said, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself is the encompassing principle of the Torah. [The translator’s explanation is that it goes farther than merely indicating that everyone is related.] For you should not say, ‘since I have been humiliated, let my fellow be humiliated.’” (Akiba’s view is similarly stated in Qedoshim Pereq 4.)

Similarly, in bTalmud Berakot 63a, Bar Kappara asks, “What is the smallest portion of Scripture on which all the regulations of the Torah hang?” [That is, may be securely based, similar to Jesus’ answer in Matthew 22.40.] The answer he gives is, “In all thy ways remember him and he will direct thy paths” (Proverbs 3.6).

Love of God and Neighbor

In the synoptic accounts of the Great Commandment it is stated (and emphasized in Mark and Matthew) that the proper summary of one’s responsibility to God is to love God and one’s neighbor. This same summary has been noted above as given by Rabbi Akiba (whose date is early second century A.D.). This combination is also found in The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, part of the pseudepigraphical writings. It has been variously regarded as a Jewish or a Christian-edited Jewish document, and thus it is not possible to be certain about its date or whether its comments represent Jewish or Christian provenance. In three places it combines the command to love God and neighbor:

T. Issachar 5:2: “Love the Lord and your neighbor, and have compassion on the poor and feeble.”

T. Issachar 7.6: “I loved the Lord with all my strength; likewise I loved every man with all my heart.”

T. Dan 5.3: “Love the Lord with all your life, and another with a sincere heart.”

In another pseudepigraphical work, Jubilees (dated about 150 B.C.), a similar statement is found in “He commanded them that they should observe the way of the Lord; that they should work righteousness; and love each his neighbor.” A similar combination is found also in Sifre Deuteronomy 323, “What did it (the Law) say to them? Take upon you the yoke of the kingdom of Heaven, and excel one another in the fear of Heaven, and conduct yourselves one toward another in charity.”

Thus it is clear that in the statements in the synoptic Gospels that summarize the demands of God’s commandments there is something happening that is similar to other Jewish discussions. Whether Jesus himself gave the combination of Deuteronomy 6.5 and Leviticus 19.18 or whether the lawyer did, as stated in Luke, others were making similar statements. However, the precise combining of these two passages as the summary of the Law has not yet been located in a clearly non-Christian work (Didache 1:2, a late first or early second century A.D. work, is clearly dependent upon the Gospels).